No Products in the Cart

Like many things in this world, boobs come in different shapes, sizes, and colors - whether you are born with those differences, chose to modify them during your lifetime, or had them medically altered.

On the other hand, any breast(s) represented in art is a very particular idea of it. No single work or artist is going to capture the whole spectrum of what it’s like in reality. Perhaps because they are conspicuous, breasts tend to congeal and parade the most important beliefs of the time and culture - especially those surrounding gender roles.

That’s why, in lieu of Breast Cancer Awareness Month, we’re looking across time and space to find works that challenge what we today think breasts should look like and do.

1. The Amazons

Block from the Bassae Frieze, c. 420-400 BC

If you’ve read Greek mythology, you may also have heard of the Amazons (has nothing to do with the Amazon Forest), a tribe of women warriors said to have lived in Scythia. Some Roman authors have argued that the name “Amazon” itself comes from the story that these women cut off one breast to improve aim on the bow - Amazones as a combination of “a”, or “without”, and “mazos”, or “breasts”.

Despite the claim, surviving images of Amazons from Ancient Greece show them with two whole breasts. Perhaps because there were many different versions of myths. What we can say for sure is that they were not just passing cameos, but were one of the most popular stories to be depicted in art - they were the biggest adversaries in the Trojan War, where Amazonian queen Penthesileia had a major lover-or-rival dynamic going on with Achilles.

Prune Nourry, The Amazon (2018)

Marble Statue of a Wounded Amazon (1st-2nd Century A.D., Roman)

While purely fictional, there is something exciting about women choosing to surrender an emblem of femininity to gain respect in the male art of warfare. That’s why artist Prune Nourry chose to reinterpret a sculpture of an Amazon woman at the Metropolitan Museum to symbolize her battles with breast cancer.

It stood at The Standard at the High Line in 2018. She was going through chemotherapy as she was creating this piece, and the red needles represent both the perils of the condition and the help from Chinese medicine (acupuncture included) - they are meant to be both menacing and healing.

2. You know Aphrodite...but do you know Ishtar?

In the ancient times, bare breasts made an appearance in images of goddesses in charge of fertility and childbirth. Imagine how important that would have been in societies surviving on agriculture and warfare (which is a number game essentially!)

So breasts in religious sculptures were largely symbolic for their maternal role in feeding a newborn life, rather than a reproduction of what real breasts look like. Which is something we often forget nowadays when, for example, breastfeeding in public ruffles feathers with people.

Statue of Aphrodite (2nd Century B.C, Baiai, Italy)

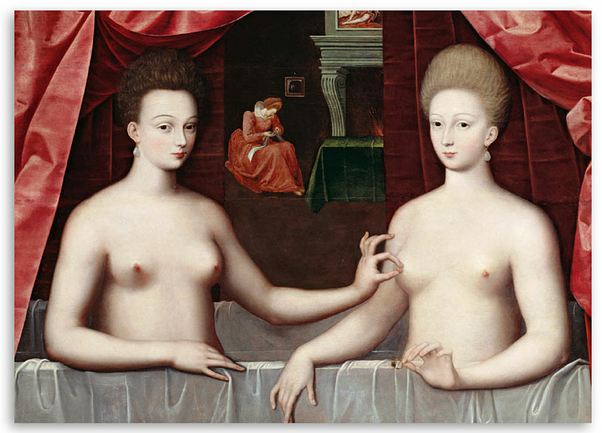

Near Eastern Art historian Zainab Bahrani suggests one theory of how that may have happened (see “The Hellenization of Ishtar: Nudity, Fetishism, and the Production of Cultural Differentiation in Ancient Art”).

She suggests that when we celebrate Greek sculptures like the famous Aphrodite as progenitors of female nude in art, it reflects a male-centered view that perceives female organs as objects of male pleasure. Along with the nonexistent vulva (Cardi B objects!!), the classical posture half-hiding but coyly half-revealing breasts, which are perfectly smooth by the way, already caters to the male gaze. On the other hand, the Babylonian Ishtar grabs her own breasts for the world to see, looking straight at us and demanding reverence to them.

3. Gita Govinda, 12th Century India

Kangra School (18th century) miniature painting

Gita Govinda (Song of Govinda) was a song by Jayadeva telling the love story of Krishna and Radha. It has very descriptive, beautiful passages, and in one of them Krishna adores and paints Radha’s breasts. While there is no sex scene in the poem per se, desire is expressed as “throbbing breasts” (!!) and Radha asks Krishna to:

“Paint, O Krishna, with fingers cooler than sandalwood, leaves and flowers with musk on this breast, which resembles a vase of consecrated water, crowned with fresh leaves, and fixed near a vernal bower, to propitiate the God of Love".

We especially like how, although Radha is a follower of Krishna’s, she quite specifically and enthusiastically asks for attention to her breasts. Seems like she knows what she wants. Which, in the Hindu context that sees desire as an expression of divinity (unlike Buddhism that aims to extinguish it entirely), is not just earthly love but spiritual awakening. The arc of Krishna and Radha falling apart then reuniting in the story is also interpreted as a metaphor for the soul wandering away from truth only to reach enlightenment by overcoming challenges.

***** NSFW WARNING *****

THE FOLLOWING SECTION IS NOT SAFE FOR WORK: genitalia, sex

4. Shunga, Edo (18th Century) Japan

What a detailed representation of pubic hair.

What is pornography without breasts nowadays? Apparently, Edo era (1600-1868) Japanese people had interest elsewhere.

When the woodblock print was invented, it gave access to prints to a much wider audience than did handmade paintings. Along with it came a genre of mass-produced pornographic prints called Shunga, because you know, people are horny like that. It became so commonplace that the government tried making a law banning all “lascivious books” in 1722, but it didn’t work.

It is interesting to observe that many Shunga don’t put much emphasis on breasts even in the most explicit scenes. If anything, much focus is on the lower part where...actual sex happens? The case remains that like in Ancient Greek sculptures, the little that we see of breasts have been heavily idealized into pretty peach shapes with no nipples at all. Idealized, but very differently compared to the breasts we see in Japanese anime today…

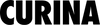

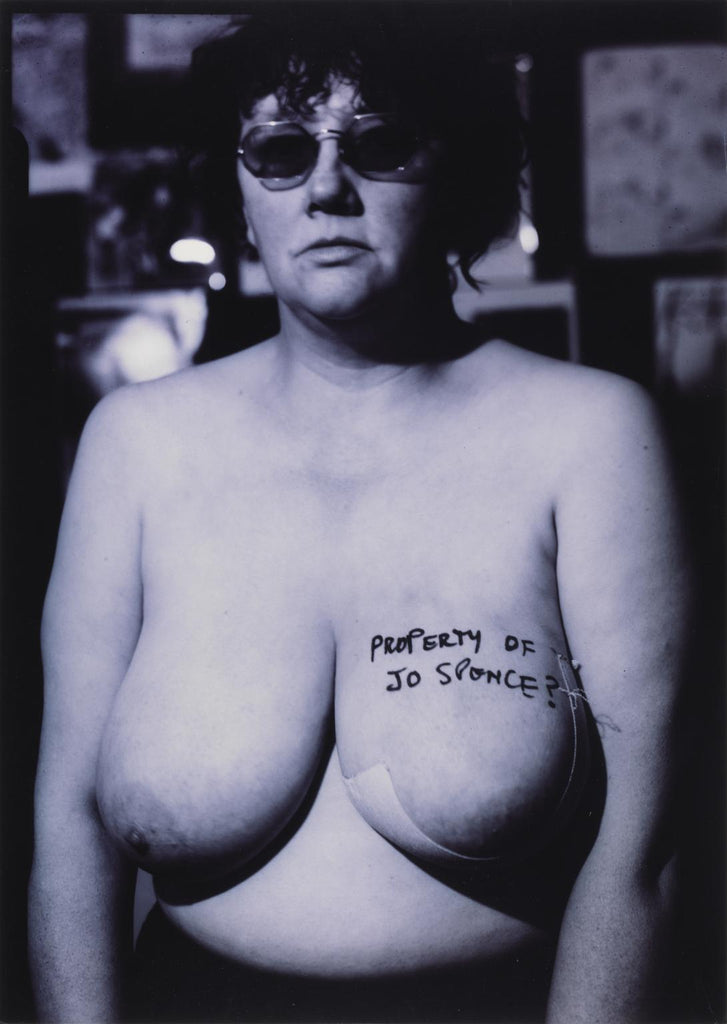

5. Jo Spence, Crisis Project / Picture of Health? (Property of Jo Spence?) (1982)

Now this one is directly related to breast cancer awareness. British photographer Jo Spence documented stages of her breast cancer treatment in a series of self portraits since her diagnosis in 1982.

In particular, she was surfacing the way in which medicine erases an individual’s history to reduce them to either normal or abnormal. As much as it helps save lives, the language we use to diagnose and discuss diseases ironically also renders many lives invisible by making them feel contaminated, damaged, or in another way lesser than average.

And that’s precisely what this self-portrait achieves: visibility. It doesn’t ask for sympathy nor anger. As Jo’s sunglasses neutralize her expression, so it does her connection to her body that exists in all its gravity whether or not you look or judge.

Sarah Lucas, Self Portrait with Fried Eggs (1996), Digital print on paper. Tate Collection

Another British artist you might want to look at is Sarah Lucas, Self Portrait with Fried Eggs (1996). Although this self-portrait has the same bold gaze as Jo’s, the take is more sarcastically humorous.

6. Senga Nengudi

Senga Nengudi, Untitled, 2011, nylon mesh, sand, pole, 60 x 48 x 18".

Senga Nengudi’s favorite material for these bulbous soft sculptures is pantyhose. They have often been compared to shapes of breasts or wombs. Pantyhose not only lets her represent different skin colors, but the way breasts hang, sag, and morph by gravity or by touch. It’s poignant that pantyhose was essentially invented to create the look of a smooth, ideal body, but it is also so elastic and malleable that it can represent natural changes to the body we try to hide. It’s such a particular look that, even when just looking at the sculptures, you can almost feel them.

It is also worth mentioning that Senga’s sculptures are not just static objects but form part of performances.

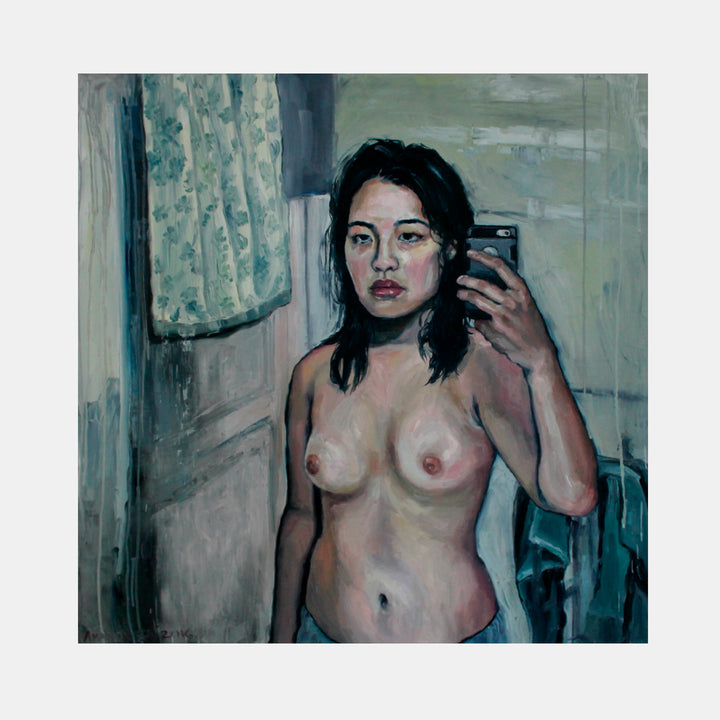

7. Drag: Breast or no Breast, that is the problem

We commonly know drag as the art of female illusion. But what kind of “female” are drag performers representing?

Rupaul’s Drag Race winners Yvie Oddly and Jaida Essence Hall.

While the more traditional camp of drag surrounding pageantry takes pride in using breast plates (usually made of silicone and can be blended into your chest) to create a convincing illusion of cis woman, others are choosing to forego them. If women’s fashion brands are making clothes that can flatter different body shapes, drag can, too, right?

In mainstream programs like Rupaul’s Drag Race, you can see how the lack of breast plates have become less and less of a point of criticism in the last few years. As the genre popularized and not only LGBTQ+ communities but straight women also become fans of drag, everyone feels supported by the fact that queens celebrate and enhance the beauty of diverse bodies.