No Products in the Cart

Meet Darryl Babatunde Smith

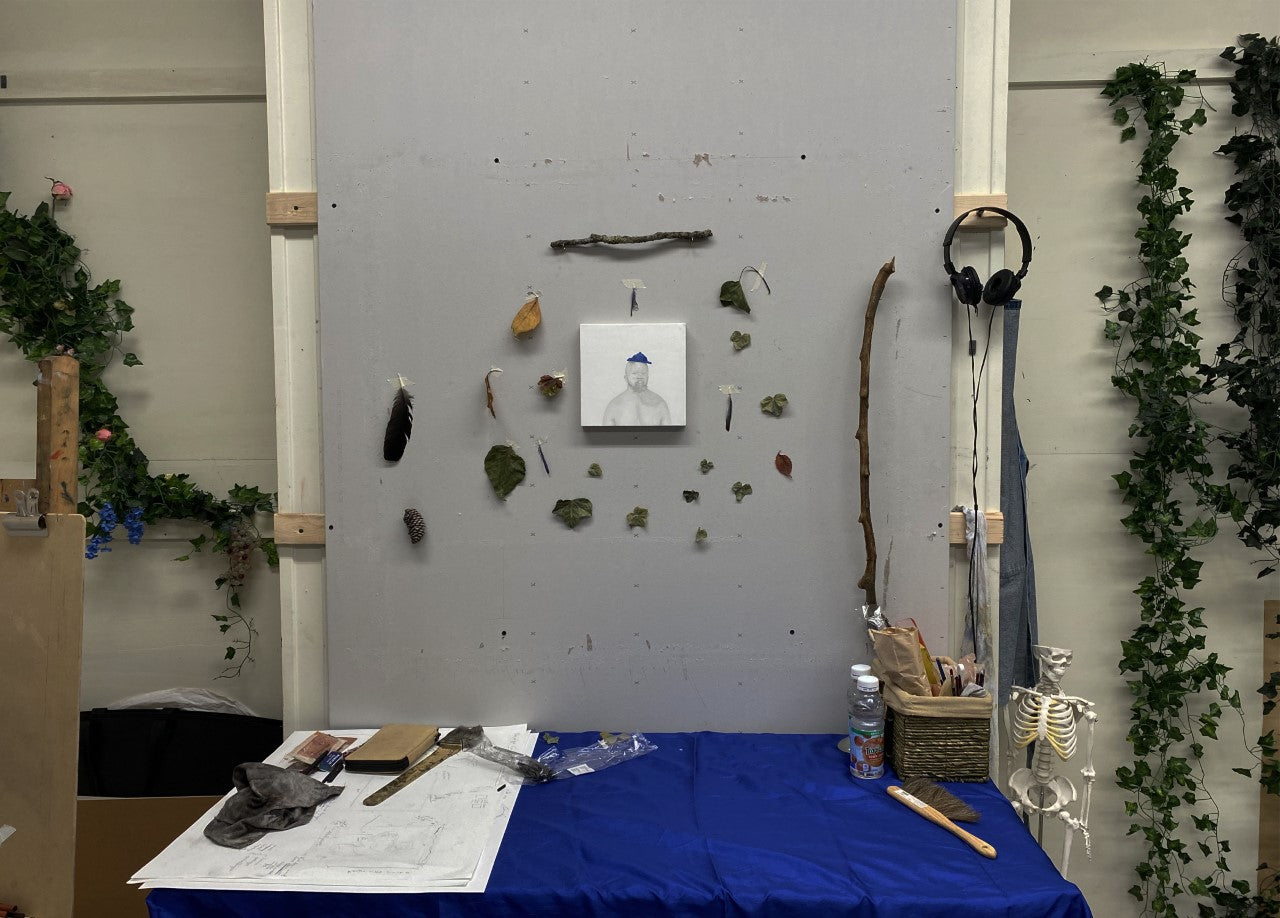

Artist Darryl Smith sits in his studio and classroom in Colora, Maryland, where he teaches boarding school students as part of an exciting residency at West Nottingham Academy.

I can see vine garlands in one corner of our chat screen, except it's not your ordinary boho aesthetic shenanigan - on quite the contrary, he has already decorated his space with his favorite key themes from Greek mythology: masks, wine, and Dionysian myth.

Darryl speaks slowly but very surely, really making each word do something instead of being pulled along by habit, like the classical scholar he is. Just like the slowness and sharp intentionality in his art, two virtues that has simply become so hard to stick to in this century.

Language

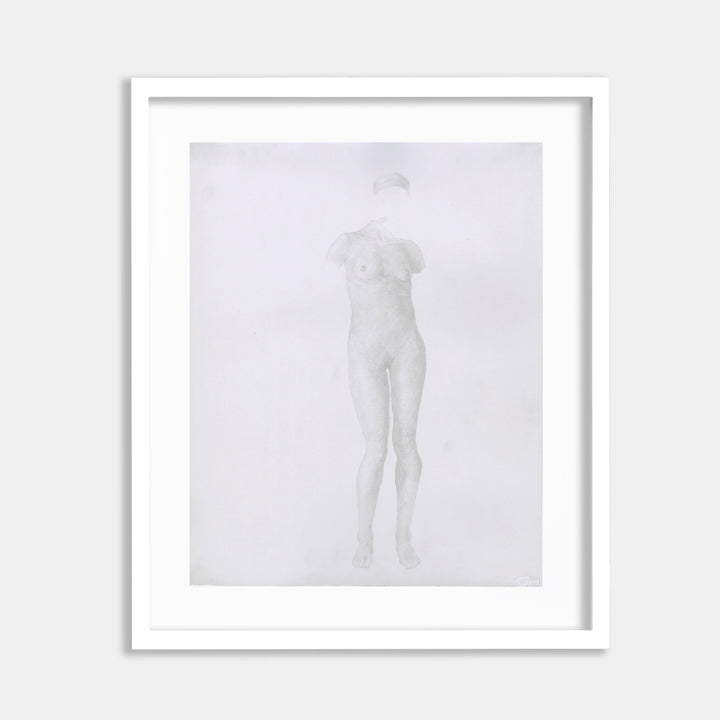

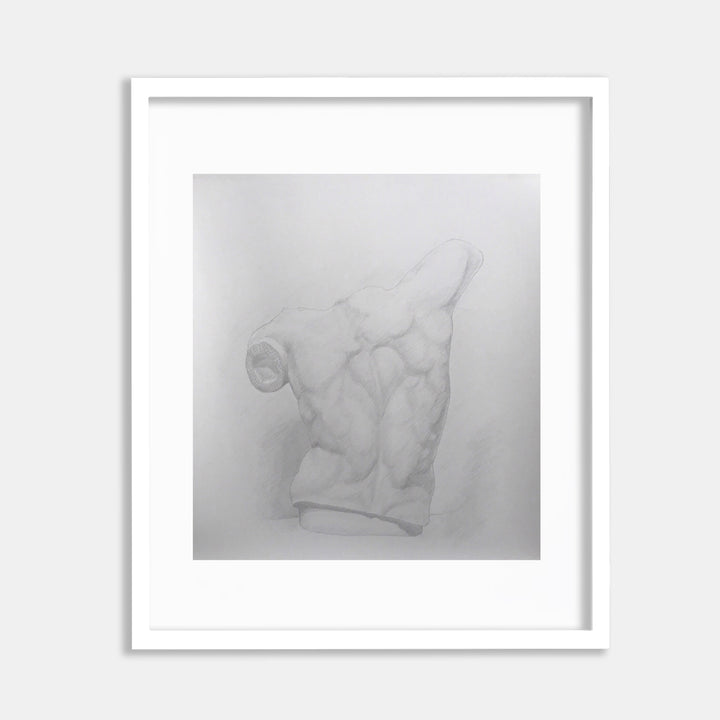

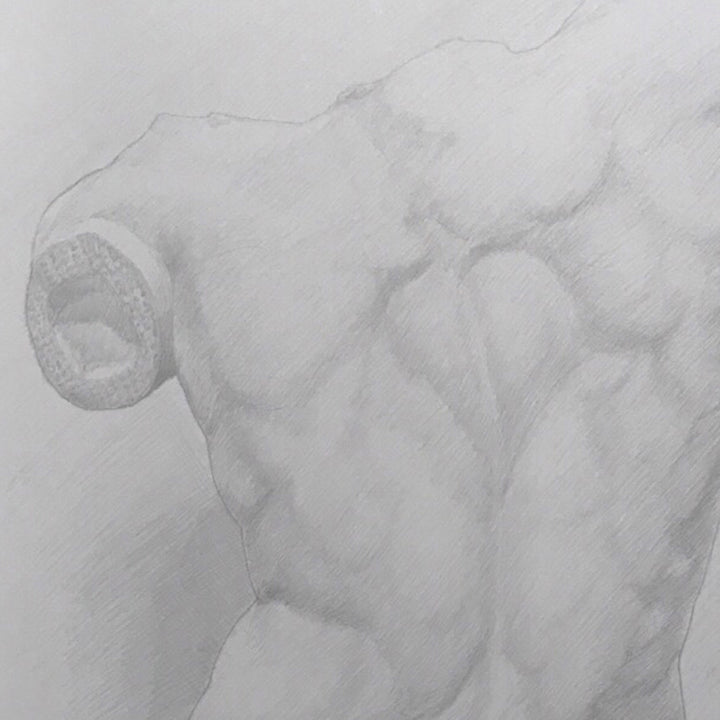

Darryl Smith, Sjálfselska/ὁ Ὄρος (Egotism/The Mountain)

Hannah: What languages do you speak and how did you become interested in them?

The number I use is 7. Three of them I’m focusing at the moment are German, Greek, and Icelandic. There’s also French, Danish, Italian, and Japanese. Although, the idea of fluency is a fluid concept.

It started in middle school when I started to learn Japanese...because anime. I was one of the few who took it seriously though, I was fascinated, for example, by how sentences could be so vague yet so specific. Then in high school I took German, French, and Latin.

Hannah: I feel that. The more languages you learn, the more aware you become of your relationship to language in general. Does art work in a similar way?

Being a polyglot, you learn how to express yourself in very different ways. With every new language I started to learn, I was fascinated not only with the language itself but the culture within. There are certain aspects in each language we can’t express in English.

And I would argue art itself is a language.

It’s the philosophy I’m bringing to high school students right now, too - what is art if not a form of communication? I can use this art-as-language analogy quite literally. Languages have adjectives, nouns, verb conjugations, dialect, or slang, and I feel all of those things have parallels in visual languages.

“Classicism”

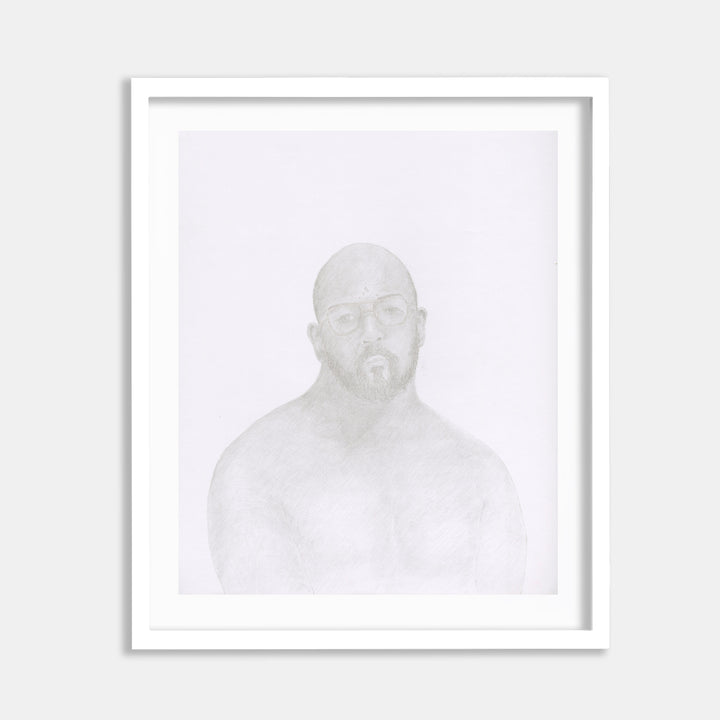

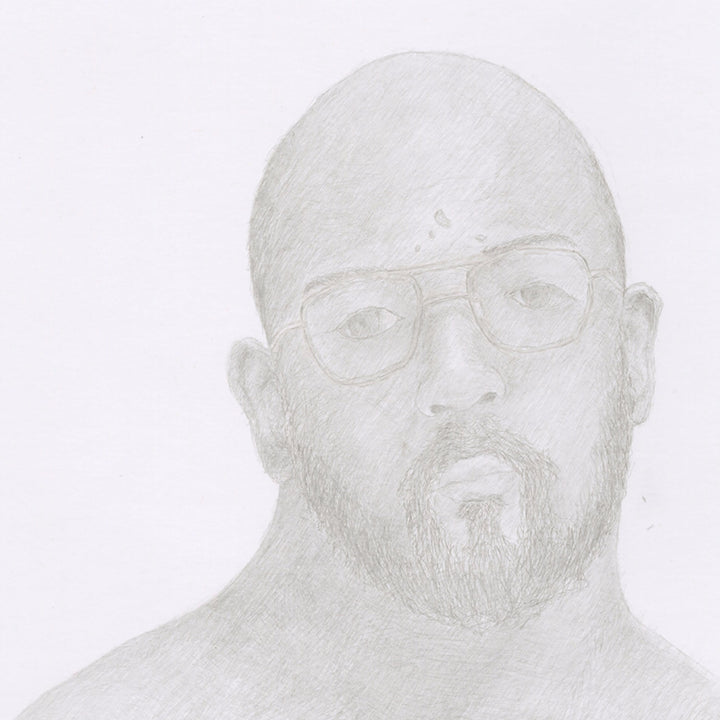

Darryl Smith, Η Οικογένεια (Family)

Hannah: It’s so rare to see this particular form of art - detailed, realistic drawings, studies of the human body, reference to historical objects - from a young artist.

To me, anatomy is the grammar of the human body. If I wanna express aspects - even intangible aspects - of people through the human body, I should know how to use it.

The way I can do it best is drawing it in the style rooted in Academic art that I was interested in my undergraduate years. At this point that style is just a tool.

I’ve tried to do more trendier, quicker stuff that people expect from a queer person of color. It just didn’t work. I would rather challenge the viewer to slow down and to appreciate my work not just as a two dimensional but three dimensional object. I take pride in the research and the planning that goes into it that takes several months at a time.

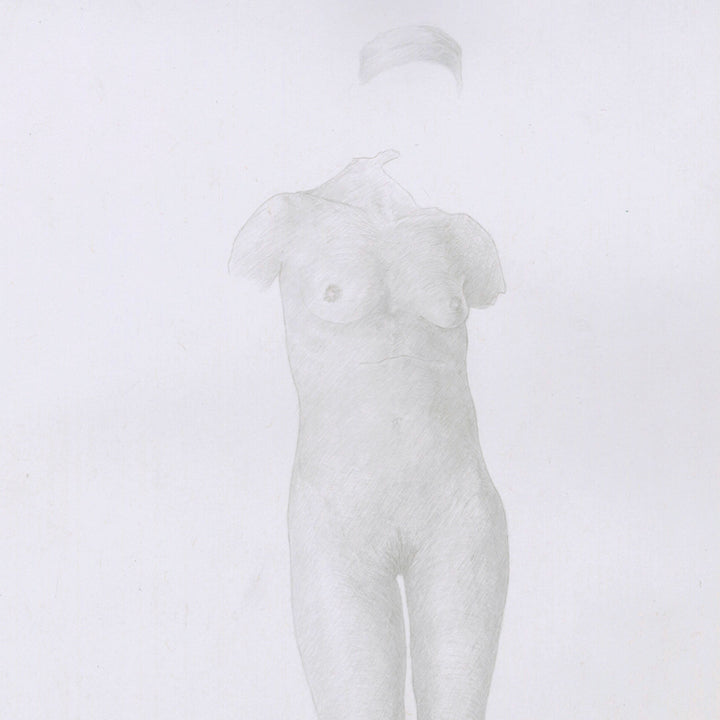

Darryl Smith, Θεά μετά διαδήματος (Goddess with a diadem)

Hannah: Why specifically the interest in Greek Classicism, and not Renaissance or 17th Century European Classicism?

Sometimes when you see something and feel like there’s more - you don’t know what it is yet, but you feel that energy…that’s why I am interested more in Greek Classicism.

I think when Renaissance took from Classical Greek art, it didn’t use it to its full potential. It’s a weird telephone effect like when you translate anything into English it doesn’t deliver the lush quality in the original language. When I’m looking at a Renaissance painting and reading the ancient text it’s based on, it didn’t really click either.

So I was like, “wait, let’s just look at the art actually made during the ancient times”. So that was my entry into Ancient Greek art - but I didn’t know exactly what drew me in until recently: body as language.

Hannah: But Classicism is in itself such a loaded word, right? No matter what it was originally, it’s so saturated with certain connotations at this point.

Right. One, we can see it as the root of Western culture.

But also, Classicism at one point became an elitist thing, what I call “Whitewashed Classicism”. There's pride there, although it’s very surface level, because if they actually knew (the culture) there would be a lot of things they might disagree with.

Whitewashing is also quite literal. We believe Ancient Greek statues were ivory white, when discoveries of traces of pigment testifies to how colorful they were supposed to be.

Hannah: If Classicism has already been so distorted, what is it that makes it particularly relevant to our time?

There are so many issues that we have been in conversation with for millenia: gender roles, transgender rights, homosexuality, education, xenophobia, women’s rights… All these things seem contemporary but there are many writings on these topics from antiquity. I think that’s so wild, almost like no time has passed.

In high school, for example, I would see girls getting bullied and having their hair pulled on. Then I’d go to the museum and see a painting from the Renaissance of Juno dragging this woman by the hair.

Ajax grabbing Cassandra’s hair. Amphora Polygnotos Group, 460-440 BCE

Detail of Jupiter and Callisto, attributed to Karel Philips Spierincks, Flemish painter active in Rome, early 17th century. (Link to the work at the Philadelphia Museum of Art: https://philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/59195.html?mulR=1774009332|61)

Hannah: Another one of those repeated iconographies is women pulling their hair in mourning.

Right. It’s a really visceral thing that hasn’t gone out.

Women pulling out their hair at Polyxena’s sacrifice. Kizöldün tumulus (520/10 - 500 BC)

That connection on a human basis is really really fascinating for me. Because of that, I see myself in these stories, these myths, these vase paintings. I don’t think these narratives are about being elite. If you actually read these stories, it would blow away the boujee connotations of Classicism.

I’ve had criticisms where people asked me “why you?” or conversations about me being an African-American male drawing from this Ancient Greek tradition in a “clean”, “Classical” art style. But I don’t know what they mean by “Classical”, because they’re referring not to Ancient Greece but something that started during or after the Renaissance.

Art as Research

Darryl working out a sketch for his new drawing „The Taste Tester”, with notes in 3 languages.

Hannah: How does your research start out? How do you choose what theme or imagery to explore in current work?

When I go to the museum, I call it „field research”. I often go about the museum asking myself lots of questions about depiction and representation:

How did Ancient Greek artisans represent someone who is dying? And how did they represent someone who has died? How did they represent someone who’s intoxicated, so intoxicated that their physical state means nothing to them? Even in the Renaissance there was research involved. Renaissance painters weren’t just painters, they were geographers, astronomers, biologists… so why don’t we still do that?

Hannah: And how do you expect audiences to unravel them?

I don’t expect viewers to know every little thing I research, but I’d like them to be open to the fact that research went into it. Because, when people call my works “Academic” or “Classical”, I don’t think they’re opening themselves up to the conceptual possibilities in the actual classical works from antiquity.

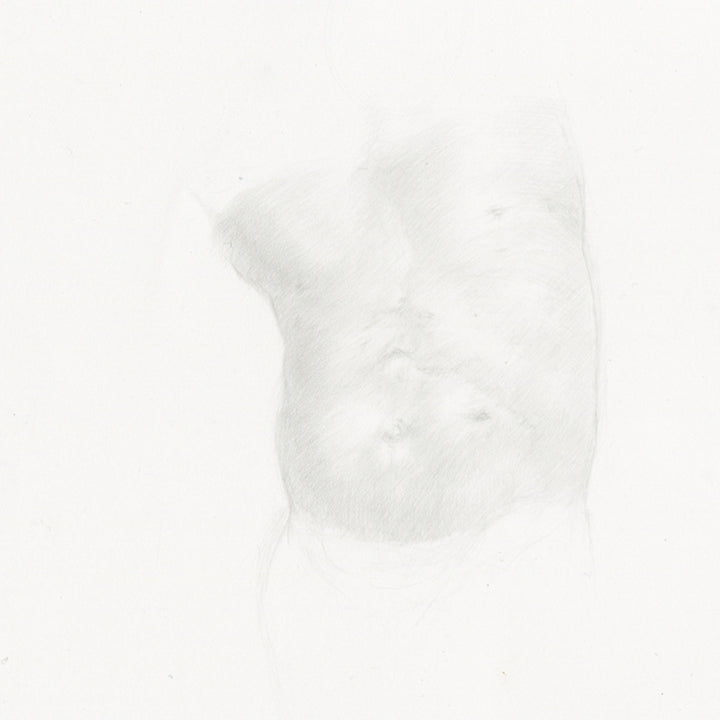

Hannah: Where do you and your body - a physically, psychologically, culturally specific body - fit into your drawings-as-research?

One is through representation of my own body. As I draw myself, I get to know myself better - it’s a healing and meditative aspect on the one hand.

Of course, the world is a bit rough lately. When we start thinking about racial politics, it’s hard not to be bombarded by sadness. I try to escape from quarantine through social media, but then bombarded by the death of people who look like me without trigger warnings. My friend calls it “apocalypse bingo”.

But then I have to step back and enjoy the fact that the culture I’m drawing from was diverse. Crazy diverse. Although people may not know that - you think classical sculptures were all white but you can literally see paint on them.

This drawing, based on a Roman wall painting, for example. If 2020 were a physical entity, I think I would look at it with this expression - the same as the irritated expression on the Roman wall painting. The mask I’m wearing is a tragedy mask. And the color blue has somber connotations too. But it’s lapis lazuli blue, so it’s a precious material as well - my materials are often slow, it can’t be erased so every line has thought put into it.

Hannah: What are some examples of your individual pieces taking part in a larger intellectual conversation?

I’ve been interested for a while in different aspects of Dionysian myth.

Masks

Wine

I’ve been drawing connections between Dionysian myths and themes we’re more familiar with today in a monotheistic society. Wine has a spiritual meaning in ancient texts, it’s to humans as ambrosia is to gods. It puts you in a different state, ectasy or ecstasis, which comes with a dance that stretches and twists your limbs so extremely that it would hurt. But this physical pain would contrast with the joy and merriment.

Violence

Dionysus is called “twice-born” because Hera had him ripped into pieces in his first life. So that violence is also reenacted in Dionysian rites, that has been compared to the breaking of bread and drinking of blood (wine) in Christianity.

Death..and Sleep?

I find this piece very suspenseful and scary. Sarpedon is bleeding out in three different areas, but we don’t know if he’s dead or not. And the scariest thing for me is that he’s being carried into the underworld by the brothers Hypnos (sleep) and Thanatos (death). My father passed away in his sleep, so when I see these two together, it feels very real.

Bronze statue of Eros sleeping (3rd–2nd century B.C.)

In coming up with the body posture, I also looked at this sculpture at the Met of sleeping Cupid. I wanted to use the language of vulnerability. This is how I use story materials from vases: to bring in other references or anecdotes of my life that mimic these situations. I am taking out the literal-ness in the original piece. I don’t think the originals were very literal anyway, there’s always a meta-narrative underneath. Doing this helps me understand the idea of timelessness.

Snake

Snakes had a positive connotation in the Ancient Greek pantheon. But it became a symbol of evil in Christianity because...you know, they took everything pagan and made them evil. This was my first drawing to put a contemporary spin on Ancient motifs.